The "Working Group for Women in Physics" of the Austrian Physical Society (ÖPG) was founded by physicist Günther Bauer on 4th December 1992. Important female physicists, such as Monika Ritsch-Marte and Claudia Draxl, enriched the working group as chairpersons. Since 2016, after the retirement of the last chairwoman, the working group now called the "Working Group for Equal Opportunities in Physics" remained inactive. In the frame of the last joint annual meeting of the Austrian and Swiss Physical Society (SPG) in September 2023, the working group was reactivated after seven years. One could almost get the impression that the topic doesn't play a major role in physics, but this is not the case, as we will explain below.

What is the current status

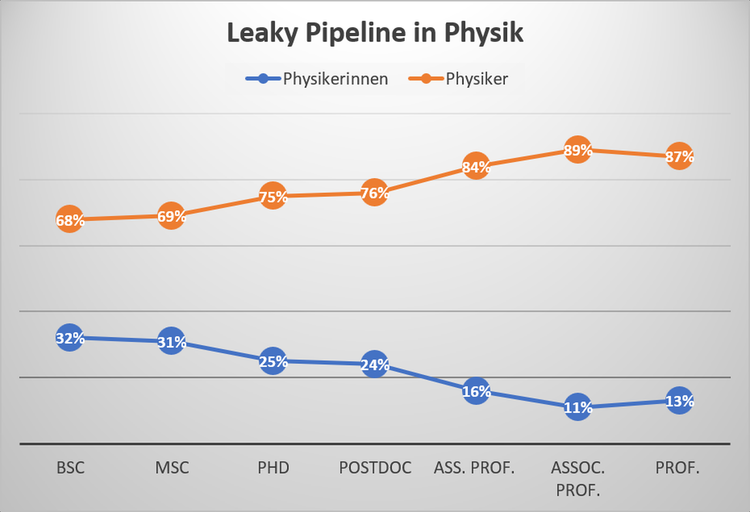

According to current figures provided on the unidata.gv.at website around thirty per cent of physics students in Austria are female. However, the number of female physicists decreases continuously with each career stage. The number of female physics professors at Austrian universities is currently around twelve percent, as shown in the graph below. This phenomenon is known as the leaky pipeline, or vertical segregation.

Back in 2009, the topic of the low number of women in physics was addressed with the lecture "How to increase the percentage of female physicists?" by Barbara Kessler at the joint annual conference of the SPG and ÖPG. The lecture attempted to explain why many young women still hesitate to study a career in physics. Among other things, it was explained that the decision is often based on social prejudices, although many of these women would be highly talented for a career in physics. Physics is considered a "male" domain in large parts of society, and breaking this stereotype has only been moderately successful to date.

Possible reasons to explain vertical segregation

In her publication called "Working cultures and gender in the natural and technical sciences - research results using the example of working cultures in physics", Martina Erlemann, Professor of Sociology of Science and Gender in Physics at the University of Berlin, gives possible reasons for vertical segregation. On the one hand, there are the high career demands in research, such as a constant availability, which are a major issue. On the other hand, important career stages, such as the PhD and the habilitation, occur often in a phase of life in which founding a family plays an important role. In a society in which women are still expected to take care of their children, an early return to work after giving birth is seen more critically than for men.

Another explanation for the vertical segregation is that women in their career seldom have a full-time position, making the integration into the physics community more difficult. But also the already well-documented disadvantage for female scientists compared to their male colleagues when it comes to peer review applications, publications and lectures also play a major role here. It is, however, also the workplace culture that influence vertical segregation, because gender differences are often only made relevant in everyday academic life.

Gendering in physics and the importance of equal opportunities

Gender should not play a role when deciding for a career in physics. Nevertheless, everyday experiences at university and in the workplace show that gendering still takes place. Two examples from Andrea Navarro Quezada illustrate this:

"When I started a new job as a postdoc in Berlin, I had to carry out measurements in a vacuum chamber that had been custom-built by a former male postdoc and adapted to his height of about 1.85 metres. When the former postdoc came to visit the lab shortly afterwards, he made the comment that I could be as intelligent as possible, but that I was simply unsuitable for the job because I was too small for the vacuum chamber. By building this 'personalised' vacuum chamber all physicists shorter than 1.80 metres were unsuitable for the job according to his logic."

"Back in Linz, when my female PhD student and I approached a former colleague about the impractical and unfriendly user interface of his self-developed software, he replied without giving it a second thought that he could colour the user interface pink for us so that we would understand it better."

Prejudice – a sign of ignorance

Male colleagues and professors in question often do not realise that the prejudices against women reflected in their comments, are a sign of ignorance that can only be compared to the misconceptions of previous centuries when women were considered unsuitable for a university career because of their monthly period or their supposedly smaller brain size. Unfortunately, such unconscious comments often result in female physicists not feeling welcome in the professional community and therefore not pursuing an academic career. Even if examples such as those described here are the exception, every derogatory comment made by individuals contributes to maintaining the status quo. Verena Auer can also report such comments:

"During my teacher training programme in physics, my fellow female students and I unfortunately experienced derogatory comments from male fellow students from time to time. For example, some were of the opinion that we wouldn't manage to get a degree, because we suppodsedly lacked the intelligence. When I was offered a position as a student assistant at the University of Salzburg, a male colleague who had been rejected said to me that I had only been taken because I was a 'quota woman'."

"Sometimes also male professors made very inappropriate comments in the physics lecture: In Salzburg, there is a memorial plaque on the house where Christian Doppler was born. The professor said that female students might had already noticed the building in question because it also houses a perfumery shop."

Create awareness

We would like to point out that we have deliberately not addressed the issue of sexual harassment, where "harmless" comments from colleagues on the appearance or clothing of female colleagues or the abuse of power by supervisors towards their female students have not been included, because a single blog post would not be nearly enough to explain the experiences in this direction.

Gender equality and the creation of equal opportunities is the goal of international political agendas and is, for example, the aim of the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations. Equal opportunities mean that anyone can achieve their career goals regardless of gender, origin, ideology, etc. Nevertheless, the above figures show us that this is often not the case.

In order to ensure equal opportunities for female physicists, prejudices and gendering in everyday physics must disappear. It will be the task of the new ÖPG working group for equal opportunities in physics to address precisely these issues and raise awareness in order to establish better framework conditions for female physicists to pursue a career in physics without the hurdles mentioned above. Because only through more awareness and the co-operation and commitment of both female and male physicists change can be achieved in the long term. (Andrea Navarro Quezada, Verena Auer, 12.12.2023)